Step Into the Scene

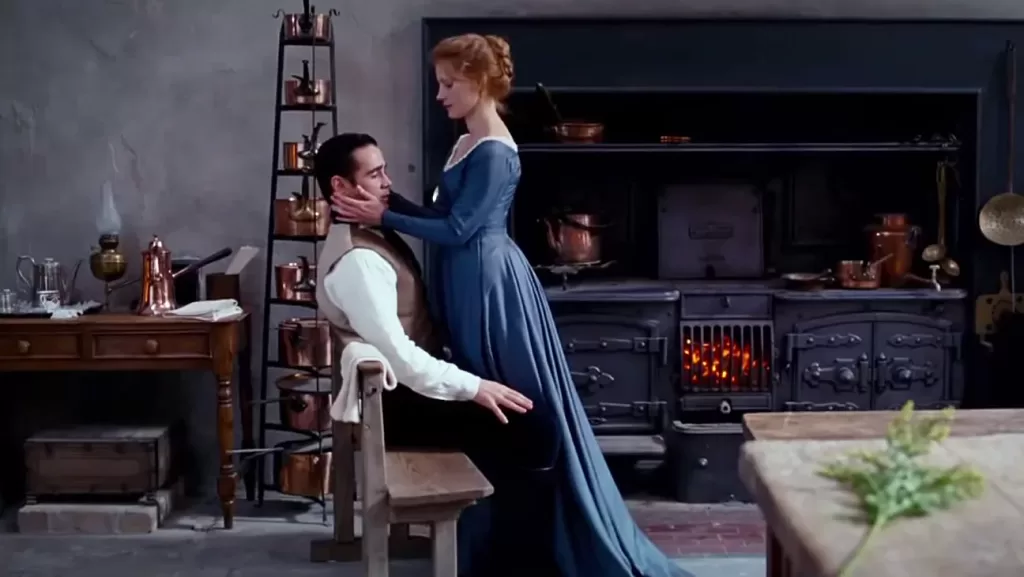

The wind howls through the crumbling corridors of an Irish estate. The house is heavy with silence, cloaked in twilight. A woman descends the stairs not softly, not demurely, but with a slow, deliberate defiance. Below, the servant waits. Not with reverence, but with the brittle confidence of a man who knows the limits of his role and how to break them.

Liv Ullmann’s Miss Julie (2014), adapted from August Strindberg’s 1888 play, is a chamber piece of power, class, gender, and the violence that pulses beneath desire. With only three characters and a single location, the film unfolds like a fevered dream claustrophobic, elegant, and thick with emotional heat.

This is not a story about love. It is a story about control, collapse, and the deep, aching loneliness of womanhood.

The Artistry: What Makes This Film Special?

Everything in Miss Julie is tightly coiled from the performances to the compositions to the space itself. The entire film takes place over one long Midsummer night inside a grand but decaying estate, its grandeur fading like the illusions its characters cling to. The cinematography lingers in cool shadows and sharp angles, the camera never rushing, never offering relief. It traps you in the room with these two people as they unravel each other with words and glances.

Jessica Chastain, as Miss Julie, gives a performance that teeters at the edge of theatricality and complete vulnerability. Her Julie is not coquettish she is desperate, wounded, and erratic. Her movements are jagged, her voice shifting between seduction and collapse. Opposite her, Colin Farrell’s John simmers with quiet fury, his resentment and ambition barely contained beneath his polished exterior.

The dialogue Strindberg’s original, sparsely adapted crackles with tension. It is not modernized. It is not made easy. And that is the point. The language feels as worn and dangerous as the manor itself. Every line is a negotiation, a performance, a trap.

The color palette of the film leans into deep blues, earthen greens, and candlelit golds, mirroring the emotional landscape: cold, rotting, and strangely beautiful. Nature seeps in through the windows moss creeping across stone, birds crying out in the distance, the weight of the outside world pressing in on this private war.

The Cultural Impact: Why This Film Still Resonates

Miss Julie is a film out of time. It resists the momentum of modern period dramas, choosing instead to linger, to simmer, to suffocate. Its refusal to entertain, to resolve neatly, or to give its heroine an escape makes it unsettling and unforgettable.

Julie is a woman of inherited power, but no agency. She performs confidence but is undone by her own longing. She is both victim and participant in her own undoing. The film does not apologize for her nor attempt to redeem her. It simply watches her, the way the house watches her, the way history watches all women who dared too much and expected love in return.

Ullmann’s direction spare, controlled, reverent makes Miss Julie not just a performance piece, but an examination of performance itself. The performance of class. Of gender. Of seduction. Of obedience.

It is not an easy film. But it is not meant to be. It is meant to be endured. And in its endurance, it leaves a mark.