Step Into the Scene

Silk slippers on marble floors. A pastel macaron held like a secret. A girl crowned too early, blinking into a court that watches her like a performance. She is thirteen. She is Austrian. She is silent when spoken to. And slowly, she becomes something else ornament, queen, myth.

Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette (2006) is a symphony of beauty and alienation. It is less a historical drama than a sensory experience bold, dissonant, and emotionally precise. The film doesn’t ask us to understand history. It asks us to understand a girl inside of it.

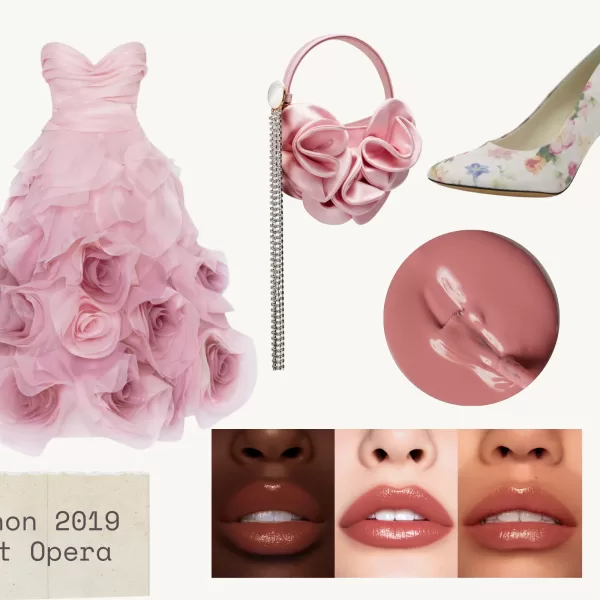

The gowns are accurate. The feelings are modern.

And the crown, from the very beginning, is too heavy.

The Artistry: What Makes This Film Special?

Coppola doesn’t dramatize the fall of a monarchy she aestheticizes its unraveling. The Versailles of this film is not dusty and gilded. It’s alive candy-colored, sunlit, echoing with the footsteps of a girl growing up in full view. The cinematography by Lance Acord is dreamy and intimate, almost conspiratorial. We are not watching history. We are eavesdropping on it.

Kirsten Dunst’s Marie is never reduced to caricature. She is not foolish, not wicked she is overwhelmed, restrained, and deeply human. Dunst gives her levity and sadness in equal measure, portraying a girl who smiles when she doesn’t know what else to do.

The costuming by Milena Canonero is legendary powder blues, rococo pinks, floral silks, and exaggerated silhouettes. The clothes speak louder than the court ever allows her to. The modern soundtrack (from New Order to The Strokes) cuts through the period elegance with intentional friction. It’s not an anachronism. It’s a mood.

Because Marie Antoinette is not asking you to look back. It’s asking you to feel what it was like to be young, disoriented, adored, and powerless.

The Cultural Impact: Why This Film Still Resonates

When it premiered, Marie Antoinette was divisive. Critics wanted politics. What Coppola gave them was interiority. She gave us a girl in a cage of velvet and lace.

Over time, the film has been reclaimed as a modern masterpiece not for what it says about the French Revolution, but for what it captures about femininity, expectation, and performance. It’s about being placed on a pedestal you never asked for, and being blamed for falling off of it.

Coppola’s version of Marie Antoinette isn’t a revisionist rescue. It’s a portrait. Unfinished. Ambivalent. Intimate. It’s what happens when you give the crown to a child and tell her to smile for the portrait.

And in the end, when she stands in the golden morning light, eyes wide and expression unreadable, we understand: she was always playing a role no one explained.

Leave a Reply